The Tudor Age

The Tudor Age

(1485–1603)

THE NEW DYNASTY. THE ENGLISH REFORMATION, HENRY VIII AND HIS HEIRS. THE GOLDEN AGE OF ELIZABETH. MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS.

Keywords, terms and concepts:

1. The Court of Star chamber

2. Thomas More

3. Cardinal Wolsey, Thomas Cromwel

4. Catherine of Aragon

5. Anne Boleyn

6. Jane Seymour

7. Anne of Cleves

8. Catherine Howard

9. Catherine Parr

10. Mary Queen of Scots

11. The Act of Supremacy (1534)

12. The Act of Union with Wales (1536)

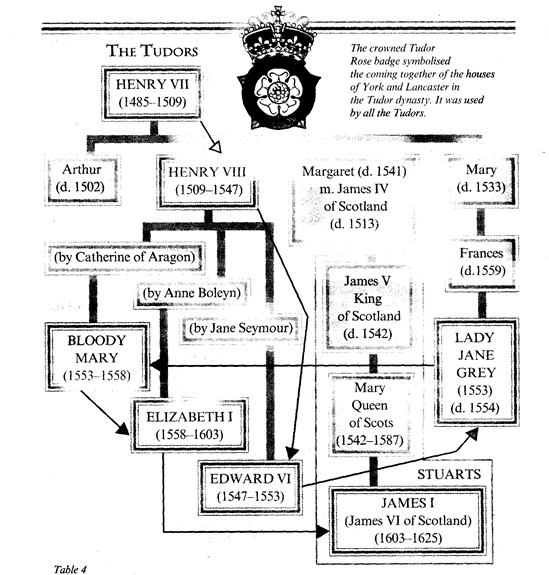

The end of the Wars of the Roses, the victory of Henry Tudor at Bosworth field and his marriage with Princess Elizabeth, heiress of the House of York (1485) were the events that symbolized the end of the Middle Ages in Britain. The year of 1485 is traditionally considered the watershed and the beginning of the Tudor Age.

In historical development the rule of the Tudors (1485-1603) with their absolute power in the long run contributed to the strengthening of its role in international affairs.

The 16th century was the age of a growing absolutism of monarchy and centralisation of the state; these phenomena facilitated the development and foundation of new capitalist relations in production.

The English type of absolute monarchy was shaped by Henry VII, who was opposed to the power of old barons. He ordered that the old castles should be destroyed (pulled down) and the feudal baronial armies should be disbanded. He was very rich with the confiscated wealth of his defeated rivals. He was strong enough to prevent any revival of armed strenghth of any group of nobles, and he enjoyed support of merchants and small landowners who had all suffered from the civil war.

These two groups, linked by a common interest in the wool trade not yet powerful enough to claim the political power were to fight for in the 17th century. They were strong enough to be useful allies of the Tudor kings and queens. Their support enabled the Tudors to become despotic rulers, while at first playing a progressive historic role.

But their reign was abundant in various controversial arbitrary developments.

The financial policy of Henry VII filled the Treasury and strengthened the throne and the church position, improved the contacts with Rome. The King skilfully steered through the complexities of European politics. His eldest son was married to the Spanish princess Catherine of Aragon, and his daughter Margaret to King James IV of Scotland.

His son Henry VIII (1509-1547) whose court was glamorous with royal games, balls and entertainments, development of culture, was among other things – a wasteful monarch, on his death his treasury was practically empty.

Henry VIII's despotism was fatal for the country's progressive minds and terrible for his family.

The king invited to court outstanding people – humanists of the Renaissance period: Thomas More – "The man for all seasons" – a play and a film with Paul Scolfield in the title role, the greatest thinker and the founder of the Utopic Socialism (1478-1535). In 1516 he wrote a book about Utopia – the best government structure on the Island of Utopia and was invited and appointed Chancellor. But Thomas More dared to contradict the King and was beheaded. That was the destiny of many a Chancellor which made the post the most dangerous in the country.

One could compare the fate of the Chancellors only with the destiny of the King's spouses, the Queens. The plural of the noun is explained by the fact of Henry VIII's record number of wives, their fate is "humorously" described by some school teachers with the following rhyme:

divorced, beheaded, died,

divorced, beheaded, survived.

1. Catherine of Aragorn was divorced

2. Anne Boleyn (mother of Elizabeth I) was beheaded

3. Jane Seymour (mother of Edward VI) died

4. Anne of Cleves was divorsed

5. Catherine Howard was beheaded

6. Catherine Parr survived him

Prince Edward, later Edward VI, Tudor

Catherine of Aragon was divorced by Henry VIII against the will of the Pope and that caused a break up with the Holy See*. The declaration of Henry VIII in 1531 that he now was Head of the Church, was an English way of Reformation, so the Reformation in England was conducted from above by the King.

* The Holly See - святейший престол.

His second wife was Anne Boleyn (1532-1536). She gave birth to a baby-girl (her daughter was Princess Elizabeth) that caused the disappointment of the King. No one could forsee the triumph of Elizabeth I. He disposed of Anne accusing her of unfaithfulness, and she was beheaded. But two days before she died her marriage was dissolved. Henry was a bachelor once more and Anne's decapitated body was buried without ceremony in the Tower of London. Ten days later the King was married again. His third wife was Jane Seymour. She died in 1537 soon after giving birth to a son and heir – Prince Edward, (to become later Edward VI) a sickly child who died of consumption in 1553 aged 15 years. Henry VIII died in 1547 and his wife Catherine Parr survived him.

Henry VIII had a powerful adviser and a skilful minister Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who was very rich and ambitious. But for all his efforts he failed to get the King a divorce from his first wife Catherine of Aragon as the Pope did not want to anger Spain and France, two Catholic powers.

Henry was outraged with his minister and the Pope. The Power of the Catholic Church in England was out of his authority and he wanted to control it for material and personal reasons. Though at the initial stages of the Reformation in Europe Henry VIII had not approved of the ideas of Martin Luther and was awarded by the Pope with the title Fidei Defensor, – Defender of the Faith. The letters "F. D." are still to be found on every British coin.

The opposition to the Pope as a political prince but not the religious leader was growing in England and Henry VIII started his own Reformation. Thomas Cromwel was his faithful reformer.

In 1531 Henry was elected the Head of the Church of England by the English bishops and in 1534 the Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy declaring him the Supreme Head of the Church of England. His Chancellor Sir Thomas More refused to recognize the Act and that cost him his life – he was charged with high treason and executed in the Tower.

With the help of his new Chancellor Thomas Cromwell Henry VIII ordered to suppress the monasteries, he captured the wealth of the monasteries that had been dissolved and destroyed. The lands of the monasteries were either sold or given to the new supporters who turned out to be enthusiastic protestants all of a sudden.

Within a few years an enormous wealth went into the empty treasury of the King.

In 1536 he managed to unite Wales with England, as the Welsh nobility were showing interest in the support of their representative on the English throne. It was the first Act of Union in the history of Britain.

His beloved wife Jane Seymour left him the long-waited-for heir Prince Edward. Mary and Elizabeth had been declared illegitimate. He wanted to achieve a betrothal of his son with the future Mary Queen of Scots who was born when Edward was 5 years old. The Scots refused the wooing of the English King as they could see through his far-reaching plans and sent Mary to France. On her return she became Queen of Scots (1561-1567).

Henry died in 1547. Though he was a gross and selfish tyrant he left his country more united and more confident than before, and his reign was glorified by the Utopian vision of More, drawings of Holbein, poetry and music of the Tudor court and other claims to greatness.

Henry VIII had destroyed the power of the Pope in England, but he didn't change the religious doctrine. He appointed Protestants as guardians of the young Edward VI (1547-1553) and they carried out the religious reformation.

After the death of Edward VI there was a highly unstable situation in the country. In his will which contradicted his father's bequest, King Edward VI disinherited his sisters and proclaimed Lady Jane Grey the Queen of England (1553). Jane Grey ruled only for nine days. But the people opposed her reign and supported the claim of Mary, the daughter of Catherine of Aragon.

Queen Mary I was determined to return England back to the Pope, as she was a fanatic Roman Catholic. She failed to understand the English hostility to Catholic Spain, and her marriage to Philip of Spain, son of the Emperor Charles V, was her own idea, celebrated in July 1554 despite the pleas of privy councillors and Parliament. Parliament had to accept Philip as King of England for Mary's lifetime; moreover, his rights in England were to expire if Mary died childless, which proved to be the case. Her marriage was very unpopular and caused several uprisings simultaneously. She crushed the rebels and pursued an aggressive policy against protestants: more than 300 people were executed in the worst traditions of the Inquisition – burned them. That is why she earned the nickname Bloody Mary.

During the reign of Bloody Mary France was the traditional enemy and England was little better than a Province of Spain. Being the wife of Philip II she got England to be drawn into a war with France and Calais, the last English possession on the continent, was lost in 1558.

Her reign and life were a political and a personal disaster. When Mary died in November 1558, deserted, unhappy and hated by many, people in the streets of London danced and drank to the health of the new queen.

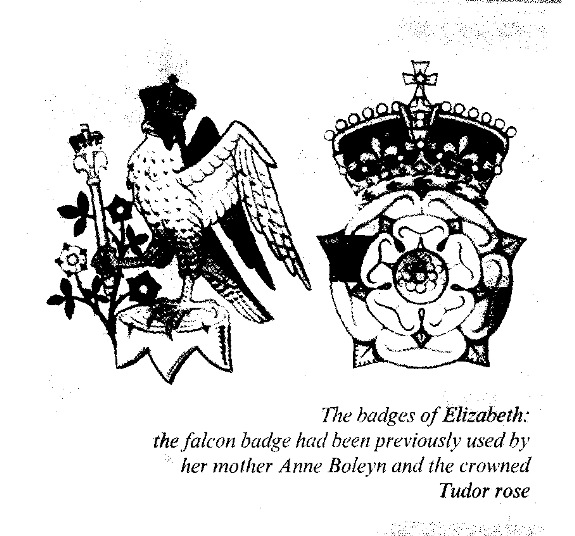

Elizabeth I, Queen of England and Ireland, daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, succeeded her half-sister to the great delight of the people.

Princess Elizabeth after her mother's execution was declared illegitimate, she spent her childhood in loneliness, and only sometimes enjoyed the company of her brother Edward, encouraged by her step mother Catherine Parr.

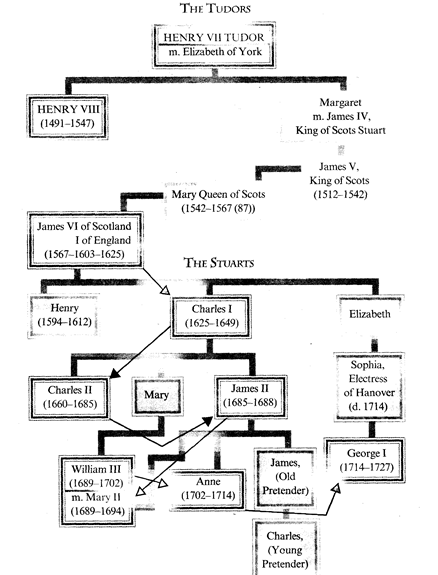

Elizabeth was a well educated, remarkable woman, who had endured the hardships other youth and succeeded to a dangerous heritage. The country was surrounded by powerful enemies: Spain possessed the Netherlands and France controlled Scotland, where the French mother of the 16 year old Mary Queen of Scots was Regent. To all the true Catholics Elizabeth still remained illegitimate, but Mary Stuart, the great granddaughter of Henry VII Tudor by his daughter Margaret was supported in her claim to the English throne as the rightful Queen of England.

Yet Elizabeth was equal to the situation. She had the Tudor courage and combined an almost masculine intelligence with an altogether feminine intuition, which enabled her to understand her people and select the right advisers.

Her first steps were to restore the moderate Protestantism other father: the Anglican service was reintroduced, and 39 articles, formulating the established doctrine of the Church, the Symbol of the Faith.

Specific differences in the development of the Reformation in England and Scotland didn't prevent the Scottish Presbyterians and the Church of England from cooperation in the conflict and struggle against the Catholics, both in England and Scotland.

The Scottish merchants supported their own variant of Calvinism, the Presbyterianism – a cheaper church founded on democratic principles of elected preachers and community chiefs. They denied the right of one man (the Pope, the King, or the bishops) to the Supremacy in Church.

The Presbyterian Church helped to secure the Independence of Scotland in their struggle against catholic France.

The policy of Elizabeth was one of compromise and settlement. In foreign affairs she continued the work of Henry VII encouraging the expansion of the English merchants. Spain was the greatest trade rival and enemy as it dominated both Europe and the New World. The Spanish Catholic kings plotted against Elizabeth in their desire to substitute Mary for Elizabeth as Queen and resented the first English efforts in the exploration of the New World.

Elizabeth was a competent diplomat and maintained the balance of power in Europe.

But she helped Dutch Protestants who rebelled against Philip II of Spain and allowed them to use English harbours. English ships were attacking Spanish ships as those were returning from America. The English captains – the "sea dogs" tried to appear private adventures – John Hawkins, Francis Drake and Martin Frobisher, but they shared their plunder with their beloved Queen.

Philip was outraged and began to build up his naval forces to conquer England.

In 1587 Francis Drake attacked the fleet in the Spanish harbours of Cadiz and destroyed a great number of ships. And that was the last straw in this undeclared war.

1587 was the most dramatic year for Elizabeth. Mary Queen of Scots was forced to abdicate in Scotland in 1567 and having left her baby son James VI of Scotland, had to flee from Scottish calvinists in 1568 and throw herself on Elizabeth's mercy. The Queen of England had no alternative but to keep her in close custody. Mary's presence in England provoked rebellions and plots to depose Elizabeth. The Spanish ambassador was involved in a plot to murder Elizabeth and expelled from the country. Then Mary herself was implicated into a similar conspiracy.

The Parliament demanded her death; and Elizabeth had to agree, and in 1587 Mary Queen of Scots was executed. But Elizabeth blamed her death on her officials.

Mary's death and Drake's raid on Cadiz both took place in 1587. The next year was to be fateful for England.

In August 1588 the Armada, the Great Spanish fleet, was in the Channel preparing to launch a full-scale invasion.

Elizabeth was at the head of her nation. She went to the Camp other troups to encourage and inspire them with such words: "Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and goodwill in the loyal hearts and goodwill of my subjects...

I know I have but the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a King, and of a King of England too".

The Spanish attempted invasion began in July, 1588. The heavy galleons of Philip's great Armada were rather awkward against the quick English ships.

The "Invisible Armada" was defeated by the English ships and the storm in the English Channel. Scattered by the winds, many of its ships were sunk or wrecked on the rocky coasts of Scotland and Ireland. It was a glorious moment for England, and Elizabeth was the heroine of the hour. But that was not the end of the war with Spain. Peace was made only after the death of Elizabeth.

James VI of Scotland, the son of Mary Stuart, didn't support Spain as he had been given to understand that his right to the English throne would be honoured.

Ireland was another battlefield of Spain in the struggle against England and Elizabeth. It was only subdued by the time other death. The best lands were captured by English landowners.

England had economic problems: inflation and unemployement. Enclosures of farm lands and wars, it produced armies of beggars and thieves, and they roamed about the country in misery and crime.

The government passed the Elizabeth an Poor Law in 1601. It aimed at putting an end to beggars of all kinds, the poor were put into workhouses.

In the 16th century the economic growth was getting faster, though still limited by feudal relations. Trade and Industry were growing. The Royal Exchange was founded in 1571, East India Company – in 1600.

Education was further developing. Many Grammar schools were founded in the 16th century. New foundations like Harrow and Rugby admitted clever boys as well as rich ones, and could rightly be called "public schools".

Elizabeth gave her name to the historical period, her reign (1558-1603) was described as "the Golden Age of Elizabeth", the most colourful and splendid in English history. She was the embodiment of everything English, and the English had found themselves as a nation.

The power of Spain was challenged on the seas and finally broken by the defeat of the Armada. Elizabeth saw the foundation of the British Empire and the flowering of the Renaissance in England. The works of Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spenser and William Shakespeare were the foundation of the English literary and dramatic heritage. Spenser's the Shepheards Calendar (1579) was a landmark in the history of English poetry, his masterpiece was The Faerie Queene (1589, 1596) which mirrored in allegories the age of his glorious sovereign the Queen, and her kingdom in Fairy-land.

In the last decade of Elizabeth's reign Shakespeare wrote about 20 plays, from Henry VI to Hamlet.

The English Renaissance has reached the greatest height in the field of theatrical Art. The Shakespeare's (drama) plays, his humanism and deeply popular realism were on the one hand produced on the basis of outstanding theatrical achievements of the period; on the other hand Shakespeare's drama made the English theatre an important contribution, achievement of the world culture treasury.

The 16th century was the century of the further consolidation of bourgeois relations. During the Elizabethan age the ideals of Renaissance embraced a broad spectrum of the population, including the merchants and citizens.

The philosophical ideas of the period were to serve the further evolution and even the revolutionary changes that came later.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) ("Novum Organum"), was the founder of English materialism and applicator of pragmatic sciences.

Literature, Art and Drama were playing an important role. In 1576 – the first theatre appeared. Public theatres were attended by aristocrats and Elizabeth I.

The 16th century was the age of transition from the medieval twilight to a more progressive age.

Questions:

1. Who were the first and last monarchs of the Tudor Dynasty?

2. What title was Henry VIII awarded with by the Pope?

3. What was the peculiarity of the Reformation in England?

4. What were the traits of continuity in the foreign policy of the Tudors?

5. Why was the reign of Elizabeth I called "the Golden Age"?

6. What threat was posed by Mary Queen of Scots to the rule of Elizabeth?