The Stuarts and the struggle of the Parliament against the Crown

The Stuarts and the struggle of the Parliament against the Crown

THE STUART KINGS AND THEIR CONFLICTS WITH THE PARLIAMENT. THE CIVIL WAR AND THE NEW MODEL ARMY. RELIGIOUS DIFFERENCES IN THE COUNTRY. OLIVER CROMWELL AND THE COMMONWEALTH.

THE RESTORATION OF MONARCHY. THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION. TWO PROTESTANT MONARCHS

Key words, terms and concepts:

1. Gunpowder Plot–Guy Fawkes (1605)

2. Puritans

3. Independents

4. Levellers

5. Diggers

6. New Model Army – Oliver Cromwell

7. High treason

8. The Rump

9. The Lord Protector (1653 -1658)

10. The Commonwealth – The Interregnum

The ideology of the rising classes in England at the beginning of the 17th century was Puritanism, it was a form of democratic religion similar to the Calvinist views: denying the supremacy of a man over religious faith, demanding a direct contact with God without any mediators, without anyone between Man and God, thus denying Church as an unnecessary institution. It was a challenge to the Church of England and the Monarch as its head, to the absolute Monarchy altogether.

The Puritan ideology was also a challenge to the cultural achievements of Renaissance – the religious doctrines rejected theatre, entertainment, pleasure, they preached and practised austerity, asceticism, adoption of puritan values against idleness. There were different varieties of puritan ideology and groups of people – the extremists, like independents (1581), insisting on complete independence of their communities, and moderates, who believed in cooperation with monarchy.

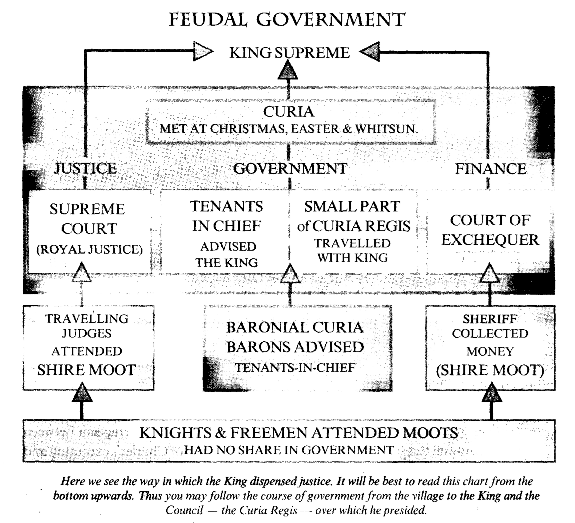

The new forces, the developing bourgeoisie began to actively oppose the absolute monarchy, particularly using the Parliament. In 1601 the Parliament made the first declaration of protest, disapproving of the Queen's sell out and distribution of licences.

Those first seeds of discord were to grow up strong and dangerous during the reign of the Stuarts; James I and Charles I.

James VI King of Scots – born in 1566, crowned King of Scots in 1567, became James I (1603-1625) of England.

On the death of Queen Elisabeth I in 1603 he became the senior representative of the Tudor dynasty, being the great-grandson of Margaret, the eldest daughter of Henry VII.

James was closely connected with the international catholic reactionary powers.

The first Stewarts had faced the alternative: either to give up absolute power and cooperate with new gentlemen and bourgeoisie or to support reactionary noblemen.

They preferred to struggle against the puritans, representatives of new revolutionary ideology.

James I, and later his son Charles I were extravagant and wasteful.

Charles I Stuart (1625-1649) was in a constant conflict with Parliament.

The Parliament, when convened, refused to give the King financial support, and Charles I ruled for 11 years without Parliament (1629-1640). That Period of Personal Government, during which the King did not receive the usual financial aid and had to raise money as best as he could: pawned Crown Jewels, gave out honours, etc.; came to an end when he became involved in a war with Scotland for which he couldn't pay.

The King (Charles I) was forced to convene a meeting of the Great Council and later to call a Parliament.

And he had to concede to this Parliament almost all that it ashed, so badly he was in need of money. Later his attempts to go back on his word and revoke his concessions and his refusal to hand over to Parliament control of the Army brought about the Civil War which his policy and that of his father had made inevitable.

The battles of the Civil War, fought as three military campaigns took place not in London, but in the counties. The King's standard was first raised at Nottingham in 1642 and, when he could not get to London, Oxford became his temporary capital, with 70 peers and 170 Members of Parliament close at hand. Oxford fell in 1646, by which time Charles had already surrendered; he passed into the hands of the victorious New Model Army (22,000 strong after 1645), which went on to take possession of London and install their commander Sir Thomas Fairfax as Governor of the Tower. His second-in-command was Oliver Cromwell, a farmer in the past and a great military leader who had organized the New Model Army. Charles I was captured by the Scots who handed him over to the Parliamentarians. He escaped and made agreements with the Scots who were later defeated by the Parliamentarian Army (1648). The English Army demanded the death of the King.

Charles I was brought to trial for High Treason, his supporters were not allowed to be present. He was sentenced to death, "and in a hushed silence on a cold January morning the King of England met his death with a courage and dignity that commanded respect." He was beheaded in Whitehall on the 30 of January 1649.

The House of Lords was abolished, some famous Royalists were captured and beheaded.

A Council of State was created to govern the country, which consisted of forty one members. The House of Commons reshuffled its members, and expelled those who had opposed the King's death.

But the troubles were not easy to stop. There was mutiny in the Army, a rebellion in Ireland, the Scots declared the son of the executed King – their King (1651) Charles II.

Oliver Cromwell ruthlessly crushed the Irish, checked the Scots, and established his authority in the Army and in the country. Admiral Blake defeated the Dutch and made England again the mistress of the seas.

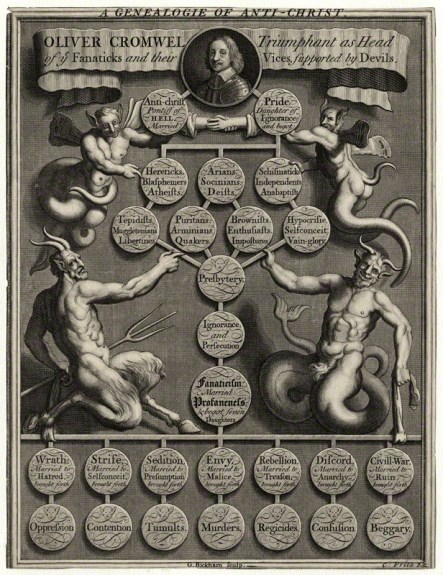

In 1653 Oliver Cromwell together with the New Model officers expelled the Rump (the Remnants of the Parliament) and established a military dictatorship. On December 16th in Westminster Oliver Cromwell publicly accepted the title of Lord Protector of a United Commonwealth of England, Scotland, Ireland and the colonies.

He didn't dare to take up the title of King, as there was opposition to that in the Army.

All in all, in four years of struggle, around 100,000 Englishmen were killed. Feelings ran high and extraordinary radical opinions were expressed both during and after the Civil War. There was a confrontation of political and religious views within the ranks of the revolutionary forces. Presbyterians had become conservative and royalist. Independents, who were represented in the New Model Army, were split.

The more extreme republicans in the New Model Army, the Levellers, as they were called, had a Manifest of their own, called the Agreement of the People, and they rallied together to defend the right of common people, they demanded the abolition of titles, and legal, political, etc.; equality in everything but property (John Lilbern).

The Diggers, a far smaller and still more radical group, opposed the private ownership of Property altogether and struggled "to set the land free" they insisted, that "the poorest man hath as true a title and just right to the land as the richest man".

The language of radicalism which burst out between 1640 and 1645 alarmed conservatives of all kinds.

Oliver Cromwell himself was a reluctant republican anxious to preserve "the ranks and orders of men – whereby England hath been known for hundreds of years: a nobleman, a gentleman, a yeoman."

However, it was the Nobility and Gentry who eventually profited from the Civil War and the Interregnum between 1649, the year of Charles's execution and 1660, the year of the Restoration of Monarchy. The Diggers failed in their ventures and the Levellers were supressed in 1649 after they rebelled against Cromwell and other army leaders. The Commonwealth, with Cromwell as Lord Protector, the period when England was a republic, is also described as Interregnum.

From 1655 England was divided not only into parishes, where the justices of the peace remained, but into districts, each with a soldier, Major-General exercising authority in the name of "godliness and virtue".

The Army was maintained by taxes imposed on the Royalists. From December 1653 until his death in September 1658, Oliver Cromwell ruled England and Scotland, he imposed temporarily a single government on England and Scotland.

In the country and in the towns the new regime closed alehouses and theatres, banned race-meetings as well as cock-fights, severely punished those people found guilty of immorality or swearing and suppressed such superstitious practices like dancing round the May Pole or celebrating Christmas.

Oliver Cromwell was a unique blend of country gentleman and professional soldier, of religious radical and social conservative. He was at once the source of stability and the ultimate source of instability. With his death the republic collapsed as his son and successor Richard lacked his qualities and was deposed 6 months after the beginning of his rule.

The generals began to fight for power, general G. Monk's influence brought about the dissolution of the Long Parliament and the new convention Parliament voted to recall Charles II and restore the Monarchy in Britain.

Charles II landed in England in May 1660 and was enthusiastically greeted and welcomed by the people. He declared a "liberty of conscience" and demanded the punishment of his father's murderers. He was crowned in 1661, his ministers were mainly old Royalists who had served him during his exile.

The Puritan Republic had been a joyless country, and the Restoration of Monarchy brought back the gaity of life: theatres were reopened, new dramatists wrote cynical plays to entertain the corrupt court. It was also the restoration of Parliament, House of Lords, Anglican church and Cavalier gentry (noblemen) with their old privileges and intolerance.

But the Commonwealth was dissolved. Charles II was the king of England and Ireland but all these countries now had their own Parliament again.

Charles II was more French than English. He did his best to secure toleration for Catholics in England and also to escape the control of Parliament. The Parliament and the Protestants wanted to keep their leading position.

The first years of the Restoration saw action of revenge on Cromwell's dead body, Acts against the Puritans passed by the Parliament of Cavaliers and the appearance of Milton's "Paradise Lost" in which the author tried "to justify the ways of God to men"; New Amsterdam was captured from the Dutch and renamed New York, after the King's brother, James, Duke of York (later James II).

The Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666 were the calamities that brought a lot of suffering to the English people.

Charles II governed the country through the inner Council, or Cabal, which consisted of five men, two of them were Catholics and the other three were supporters of religious toleration. As a result Charles issued a Declaration of Indulgence granting toleration to all – including Catholics. In their rejection of that Declaration the Parliament adopted the Test Act (1673) forbidding all Catholics to hold office for the Crown. It was also directed against James the Duke of York, the heir to the throne.

The Opposition to the King became organized into a party with a majority in the newly elected Parliament. They managed to pass the Habeas Corpus Act (1679), which provided a protection of human rights of the new bourgeoisie. Ibis Act, originally adopted against the arbitrary actions of Charles II, has proved to the be an essential milestone in the legal system of Great Britain.

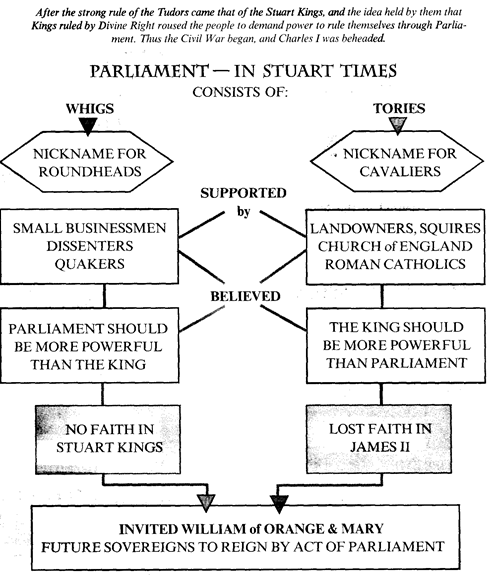

Newly coined nicknames became applicable to the opposing groups in the political struggle: the opposition to the King which demanded a further curbing of the Monarch's prerogatives, was nicknamed "The Whigs" by their opponents in Parliament. These opponents supported the Catholic views of the King and the King himself; and they in their turn were also nicknamed as "the Tories" by the first group. It was another term of abuse originated for condemning the Irish Catholics who were fighting against the Protestant army of Cromwell. These two parties, the Whigs and the Tories became the basis of Britain's two-party parliament system of government (see Chart III, p. 46).

James II became the King of England after his brother's death in 1685. He had two daughters – Mary and Ann – from his first Protestant wife, and they were firm Protestants. Mary was married to her first cousin, William of Orange, a Dutch prince and a militant Protestant.

James II

William III and Mary II

When the Catholic second wife of James II gave birth to a baby son, the English Parliament and the Protestant bourgeoisie were alarmed by the prospect of Catholic succession of Monarchs.

Tones, Whigs and Anglicans began to look for a Protestant rescue. They invited William of Orange to invade Britain. The forces of William landed in England and that decided the issue: James and his family fled away from the country. The Parliament decided that James II had lost his right to the Crown.

Mary and William began to reign jointly, moreover, the Parliament decided that William would rule on in the event of Mary's prior death.

The political events of 1688 were called "the Glorious Revolution" as they had realized the bourgeois theories of the nature of government (John Locke (1632-1704)) and the demands that the powers of the King should be restricted and that the Parliament should be overall power in the state.

Though some historians insist on calling it a coup d'etat of the ruling classes, the changes are recognized as a historic turning point in the conception and practice of government. In point of fact it can be justly regarded as a "glorious compromise" between the new bourgeoisie and the old feudal institutions like the Monarchy, the House of Lords, etc, but also in imposing new bourgeois parliamentary privileges and relations. The Parliament secured its superiority by adopting the Bill of Rights in 1689 and the Monarchs – William III and Mary II accepted the conditions advanced by the Parliament:

- the legislative and executive power of the Monarchs was limited. The Bills passed by the Parliament were to be subjected to the Royal Assent, but the Monarch could not refuse to sign there. The Monarchs could not impose taxes,

- the Army could be kept only with the Parliament's permission.

In 1701 the Parliament passed the Act of Settlement that secured Protestant succession to the throne of England and Ireland, outlawing any Catholic Pretenders. The Act stipulated that if William and Mary had no children, the Crown should pass to Mary's sister Anne. And if Anne died childless too, the Crown should passto Sophia Electress of Hannover, the granddaughter of James I Stuart, or her Protestant descendant. The Act of Settlement is of major Constitutional importance, it has remained in force ever since.

Praising the "Glorious Revolution" as "great and bloodless", historians have to admit, however, that it was bloodless only in England.

In Ireland there was a blood bath of war between the Protestants of Londonderry and the Catholic Irish Parliament. King William III landed in Ireland with the British, Dutch, Danish and Huguenot troops and defeated the Irish and French army of James II in the Battle of the River Boyne (1691).

James left Ireland for France and never returned to any of his kingdoms. The defeat in this Battle crushed the Irish hopes for independence, the Irish Catholics lost all the rights.

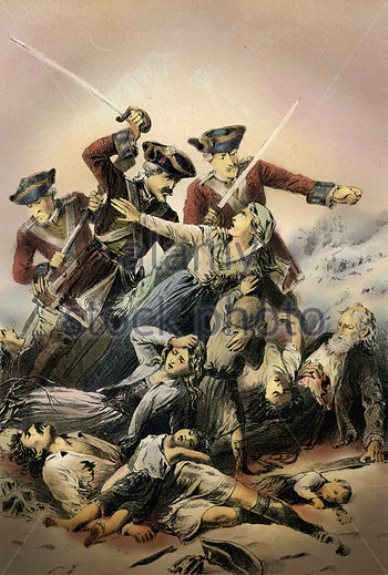

In Scotland William was recognized in the Lowlands. But in the Highlands a revolt rose and the loyalty of the Highland chiefs was bought with a large sum of money. The chiefs were to swear an oath of loyalty to the new King, but one or two were a few days late, among them Maclau MacDonald of Glencoe. This was severely and brutally punished by a company of troops, who were sent to murder all the MacDonalds of Glencoe under 70. 36 Men, women and children were killed as they slept, and their houses were set on fire. Those who escaped told the world of the Massacre of Glencoe.

The French and Jacobite gazettes condemned the King's Government as cruel and Barbarous.

The "Glorious", "bloodless" revolution was a political readjustment of the government in the interests of the ruling classes, but it did not involve the majority of the population.

Massacre of Glencoe

William of Orange used the strength of England in the interests of his native country – Holland in the wars against France. "King William's War" (as the English called it) prevented another threat of invasion of Britain, but it didn't bring peace to Europe.

The seventeenth century was the age of the Stuarts – their rise in 1603, their tragedy and defeat from 1648-1660, their restoration in 1660, their constant struggle against the Parliament which resulted in their forced compromise and the victory of the Parliament, the victory of the new ruling classes.

The Civil war and the United Commonwealth, the rule of Oliver Cromwell as the Lord Protector and the leader of Independents and Puritans were the events in the middle of the century and are described as the Interregnum. It was a highly dramatic and tragic period of British history.

The economy of Britain by the end of the century was developing freely, new economic institutions like the Bank of Britain (1695) were founded. Trade and colonies were flourishing. The East India Company was the greatest corporation in the country.

The religious struggle and conflicts gave freedom to all Protestants.

After the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London came the efforts of Sir Christopher Wren and the achievements of science made by I. Newton and other members of the Royal Society.

By the end of the century Britain was becoming a prosperous country.

Questions:

1. Why were the Stuarts inheritors of the English Crown?

2. What were the reasons for the conflict of the first Stuarts with the English Parliament?

3. How did the Civil war develop and end?

4. What social groups supported Cromwell?

5. What was the policy of the United Commonwealth in Europe and in the world?

6. What were the reasons for the Reformation of Monarchy in Britain?

7. What were the Acts of Parliament directed against the Kings and flow did they develop the social situation in Britain?

8. When did the political parties appear in Britain and how?